One-person plays are a gamble. The singular actor takes on the mammoth task of holding an audiences’ attention for sixty to ninety minutes. One-handers are a style of performance with myriad limitations, but it is precisely these limitations that offer theatre-makers and actors the opportunity to think outside the box and stretch their performance muscle to the fullest.

I love one-person shows for precisely this reason, but it is their hit-or-miss nature that always makes me nervous to watch them. The theatre scene in South Africa abounds with one-person plays because they are usually the most financially viable, making them easier to stage and travel with to festivals. In my three and a half years in Cape Town I have experienced my fair share of one-person shows, many of which leave me feeling uninspired and yearning for more; others which fan the flames of my creative passion and remind me why I am pursuing theatre as a career.

In recent weeks I experienced two of the most exceptional pieces of theatre (and art) in my brief but significant time as a watcher, maker and scholar of performance art. The first was Isidlamlilo: The Fire Eater, a play about a woman living in a hostel in Durban who is later declared dead by the Department of Home Affairs. The story follows her life as an IFP (Inkatha Freedom Party) assassin and the myth of the Impundulu Bird (The Lightning Bird) that surrounds her life and political career. The second play and the subject of this essay, Kafka’s Ape is an adaptation of Franz Kafka’s A Report to an Academy. The short story follows the life of Red Peter, a human who gives a lecture recounting his previous life as an ape and his assimilation into human society.

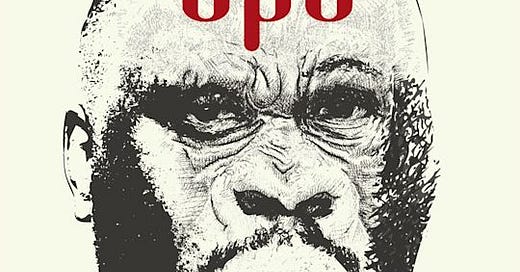

Tony Miyambo as Red Peter (Kafka’s Ape, 2025).

Directed by the brilliant Phala Ookeditse Phala and performed by the incredible Tony Miyambo, Kafka’s Ape translates the short story onto the stage through an impressive display of physical theatre. I watched in awe as Tony remained on his toes for the entire ninety-minute performance, only standing flat-footed when depicting one of Red Peter’s captors. As Red Peter addressed the Academy, I marvelled at Tony’s vocal dexterity and the way he interspersed his speech with grunts, squeals and other ape-like sounds. As if the actual performance was not impressive enough, the contents of his address left me with food for thought that I am still trying to digest.

The most significant moment in the play, and what I took to be the central theme, is when Red Peter discusses his desire for a “way out”:

I’m worried that people do not understand precisely what I mean by a way out. I use the word in its most common and fullest sense. I am deliberately not saying freedom…among human beings, people all too often are deceived by freedom.

The image that precedes this sees Red Peter crouched beneath his lectern, his walking cane and the staff of the lectern framing the cage his captors keep in him. His way out is a literal way out of the cage, but also a way out of his predicament, an escape from his path to lose his ape-nature and become human.

Without the greatest inner calm, I would never have been able to get out.

Slowly, as Red Peter observes the behaviours and habits of his captors, he learns to become human, accepting his fate and realizing that even if he tried to escape or succeeded in escaping from the cage, his captors would lock him back in.

I had to find a way out if I wanted to live, but that this way out could not be reached by escaping. I no longer knew if escape was possible…

My immediate interpretation of this scene was of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. Red Peter’s imprisonment reads as the kidnapping of black Africans and their violent journey towards colonial Europe to be used as slaves. The ape’s eventual assimilation to humanness runs parallel to Africans’ forced assimilation to whiteness and/or Europeanness, leaving behind centuries of rich African culture and ways of being. The hopelessness of enslaved people is captured in Peter’s thoughts of escaping:

No sooner would I have stuck my head out, that they would have captured me again and locked me up in an even worse cage…Or I could have managed to steal my way up to the ocean and drowned. Acts of despair.

This interpretation is significant precisely because what follows is that core sentiment “I had to find a way out”. When Red Peter states emphatically that he is “not speaking of freedom” I couldn’t help but think towards the way in which many people who yearn for a better world, long for a freedom that is still confined by the limits of our modern society. Be it the economic shackles of capitalism or the cultures of modernity that we accept as our world order, the phrase “humans are too often deceived by freedom”, stands out as a critique of a dormant imagination that cannot dream or reify a world beyond our current one.

If freedom in our day does exist, it manifests as the acquisition of more money (a better salary), improved living standards, and fewer social and economic disparities. It is not, however, a full liberation from the structures that keep us in these perpetual states of longing. If anything, that longing magnifies the illusion of freedom, hypnotizing us all as our shackles tighten and our spines curve further downwards. Whilst Peter’s critique of freedom rings true of contemporary society, him finding a way out is itself a contradiction. His assimilation to humanness is an act of survival not an expression of liberty. The contradiction highlights the liminal space Red Peter occupies as “a human in waiting”, and in this liminality is exactly where Peter’s intelligence, insight and complexity resides.

No, I didn’t want freedom. Only a way out – to the right or left or anywhere at all. I made other demands, even if the way out should be only an illusion.

As a South African production, I instinctively interpreted the first half of the play through the racial history of the country. But upon reflection, I realized that the brilliance of Kafka’s Ape is its transcendence of race and other social stratifications. This essay is an interrogation rather than an analysis because the play’s universality and thematic nuance has left me with more questions still worthy of investigation. As a reviewer from the Daily Maverick, a South African newspaper stated, “the simplicity of the story hides layers of complexity that speak intimately to the universal human experience”.

To some, the crux of the story might be Red Peter’s contradiction, or perhaps duality. Even after participating in all the human endeavours, drinking, shaking hands, and learning how to speak, he remains an ape. As Red Peter approached the audience to shake our hands, he picked up the foot of the person and pinched fleas off the heads of the people in the front row as part of his greeting. His semi complete assimilation to humanness is comedic and pitiful, a contradiction once again; the former feeling demonstrating our recognition of his humanity, the latter one emphasizing our perception of him as a creature trying to be something he is not. And yet, in our pitiful perception of his non-humanness, it is also that we appreciate his profound humanity. One that not only rivals ours but makes us question whether those qualities of empathy and compassion are even innate to humankind. How could I forget the scene where a crew member of the ship burns a cigarette into the ape’s back?

He held his burning pipe against my fur…until it began to burn…He wasn’t angry with me. He realized we were fighting on the same side against ape nature and that I had the more difficult part.

Red Peter’s humane character is what I left the theatre with, and it’s worth noting that his sense of justice and compassion is emphasized in additional performance text not found in the original short story. As it concludes, Tony’s performance seizes the hearts of the audience. He even briefly mentions Palestine and Sudan as he raises his arms to the sky, calling upon the audience to find practical solutions to our contemporary problems. A warm, orange light beams down upon Tony’s sweat-drenched face, and the play ends, leaving the audience forever changed.

P.S:

I highly recommend reading Kafka’s A Report to An Academy. It is a brilliant short story, one worthy of analysis as a stand-alone text. It is available online, @FranzKafkaOnline. Thanks for reading.